Dance can be accessed and appreciated in a number of different modalities, from the lived experience of the dancer to the audience-member spectator who does not have sustained and expert dance training and exposure themselves. If you think of dance as something that comes from the inside out you are more likely to think of dance as a kind of curated movement, as something that is expressive and that results in a dance output that takes place in time. If you think of dance as something to be watched and appreciated without moving yourself, and without the sort of empathetic, imaginative mirroring that trained dancers often have while watching dance, then visual perception of dance comes to the fore.

When people in the dance world refer to a dancer’s “lines” they are referring to the visual lines of geometry, both static and in motion, that can be seen at the site of a dancer’s body. When they say that a dancer has “clean lines” they mean that their dancing exhibits visible geometric lines that can be seen by the viewer easier without imprecision or fuzziness (no coloring outside the lines).

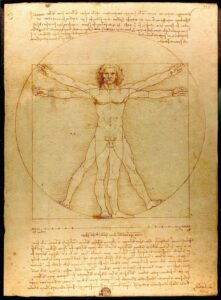

The first book that I had on ballet was called The Classic Ballet by Lincoln Kirstein, which demonstrated classical ballet positions and forms with illustrations. I spent some time as a pre-ballet child trying to make my body into the shapes that appeared in that book. I’m not sure if it was in this book or in another, but I also recall an illustration of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (L’uomo vitruviano in Italian, c. 1490 – see illustration at the end of this post), that would remain ballet-connected in my memory forever. It demonstrated the horizontal plane that ballet often uses – one in which movement, positions, lines flow as if you were sandwiched between two boards to the front and back and could only move within them.

Of course, the horizontal plane isn’t the only one in which dance movement takes place. It is true, however, that one can map ballet ideal movements and positions with geometric images. Dancer, choreographer, educator and innovator, William Forsythe, for example, has codified a distinct approach to dance that sees the possibilities for dance improvisation along geometric lines. As such, his work has also been part of architectural and performance art installations in museums and exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe. (For more on Forsythe’s bio see https://www.williamforsythe.com/biography.html.) His video lectures on this can be found on his website here: https://improvisation-technologies.zkm.de/intro/.

For formal, codified types of dance like classical ballet, the quest for perfect lines is one of the standards that can make it difficult for a person with a body that doesn’t well lend itself to visible geometric lines (one that can’t achieve the hip or shoulder rotation for certain geometric forms, for example) can be ill-adapted to be able to achieve certain dance ideals. As the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato noted in his discussion of Forms, human beings can only approximate, but not achieve perfectly, the ideal Forms that exist in the universe. Ideal Forms, the perfect versions of the balletic images and movements sought, for example, are available not to us but to the gods. Getting very close to perfection is the best we can do, and for some this isn’t possible at all.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man

Leave a Reply